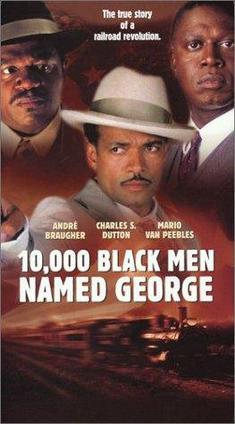

10,000 Black Men Named George

10,000 Black Men Named George was a 2002 award-winning, made-for-television movie, not a documentary. With gripping and skillful direction, writing and acting, the movie not only brought to life the 12-year organizing struggle (1925–1937) for the first all-Black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. It captured the power, savviness and complexities of Black men and women fighting for higher wages, better working conditions and dignity on the job against a company and a racist class system stacked against them.[1]

Synopsis

Asa Philip Randolph, a Black journalist and socialist trying to establish a voice for these forgotten workers, agrees to fight for the Pullman porters’ cause and form the first black union in America. Livelihoods and lives would be put at risk in the attempt to gain 10,000 signatures of the men known only as “George.”[2]

Black Empower

The film underlined the crucial role of Black workers and Black communities in the fight for economic justice and the struggle against racism which could be the new spirit to fight for Black Lives Matter. One of the most engaging and relevant scenes in “10,000 Black Men Named George” comes when Totten seeks out Randolph to convince him to lead the organizing drive for an independent union. Randolph asks Totten “Do you think America is ready for a colored union?” Totten’s answer encapsulates the Black freedom struggle for the last 400 years. Totten responds, “I don’t think America is ready for anything. Unless we make them ready.”

Controversy

At the beginning of the film, there's a scene where they point out a stereotypes about white women using their whiteness and femininity as a weapon against Black men. The racist trope that Black men are somehow a threat to or dangerously attracted to white women has been reproduced among white men and women through the generations. As the film begin, a white woman passenger doing something illicit, stealing Pullman towels, which is witnessed by a white-jacketed Black porter. In the advanced, and sometimes dangerous, calculus of white women/black men relations, the porter has to figure out what to do. Say something or not. He will get docked pay for missing Pullman property. When porter talk to her, the woman call the conductor and accuse porter for threatening her and demands protection, which leads to firing.[3]

Not only is the porter being ripped off by the company and losing wages but the larger racist codes are at work in the workplace. Social and economic dynamics confront Black men and women in the workplace on an hourly basis.