Fort Benning

Fort Benning was named under a general in the Confederate States Army, Henry L. Benning. He also was a lawyer, legislator, and judge on the Georgia Supreme Court.[1] Fort Benning is one of ten U.S. Army installations named for former Confederate Generals.

Fort Benning is located in an area commonly known as the "Tri-Community", comprised of Columbus, Fort Benning, Georgia, and Phenix City, Alabama. Dubbed the US Army Maneuver Center of Excellence, Fort Benning is home to Basic Training, Airborne, and Ranger School.[2]

History

Fort Benning, the Home of the Infantry, was established as Camp Benning in 1918 on an old plantation site. It was assigned the mission of providing basic training for units during World War I, and briefly the training of tank units. In 1920 Congress funded the post as a permanent installation, with new construction, and the establishment of the School of Infantry. In 1922, the post was renamed Fort Benning, and throughout the 1920s and 1930s Benning was the location of a great many reforms and improvements that transformed the Infantry from a 19th military to a 20th century one. In World War II, Fort Benning was a primary infantry and airborne training center as well as an officer candidate school. By war's end Fort Benning had developed and refined new infantry and combined arms tactics based on combat experience.[3]

Fort Benning was also where the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the first all-black unit of paratroopers, trained. At the time, the Army was segregated, with black soldiers generally placed in cleaning or serving positions. The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was the first of its kind, an all-black paratroop battalion, nicknamed the "Triple Nickles." They were used as smokejumpers, fighting forest fires ignited by Japanese balloon bombs on the West Coast, becoming their other nickname, the 555 "Smoke Jumpers."[3]

In 1950 Fort Benning became the home of the Ranger School, which continues at Benning to this day. In 1963, the Eleventh Air Assault Division was formed to develop, test, and use the Army's new helicopter-based air assault tactics, which have continued to be central to airmobile infantry operations. For many years military dog training was conducted at Fort Benning, particularly scout dog with counter-ambush training. Fort Benning continues to be a central training post for officers, non-commissioned officers, airborne infantry, and basic Ranger school.[3]

Controversy

As a result of national protests following the May 25, 2020 murder of George Floyd, an African-American man, at the hands and knees of the Minneapolis police, Congress began to evaluate Democratic proposals to strip the names of Confederate leaders from military bases, including Fort Benning.[4]

Brigadier General Henry L. Benning was acclaimed as "Old Rock" by his men. He once had two horses shot out from under him in battle. Harold Holzer calls him "a pretty formidable military commander. That is, effective in the war to perpetuate slavery. More to the point, he was a virulent white supremacist who issued incendiary warnings about the so-called dangers of having free black men outnumbering white men and threatening the purity of lily-white womanhood."[5]

Triple Nickles

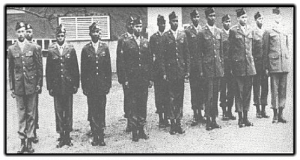

The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, also known as “the Triple Nickels”, was the first all-Black unit of paratroopers. Starting in 1943, they trained at Fort Benning during World War II, when the U.S. Army was still segregated and Black soldiers had only the support roles of serving and cleaning up after White servicemen. The Triple Nickels were used as “smokejumpers,” courageously fighting forest fires ignited by Japanese balloon bombs (a.k.a. Fu-Go bombs) that landed on the West Coast.[5]

The distinctive insignia for the 555th was a white parachute with a black panther crouching on top. At Fort Benning, the unit's Black officers and sergeants were not welcomed in the base and noncommissioned officers' clubs. After demonstrating that they were capable paratroopers, the Triple Nickles trained, worked, and ate together with some degree of solidarity with their white counterparts. Off-base, they continued to encounter discrimination, segregation, and police abuse.[6]

The 555th continued to experience racism in Oregon. The base commander made it clear that he disliked having an all-Black unit, and it was reported that only two Pendleton bars and one Chinese restaurant would serve unit members. The unit spent most of its time on base, learning how to disarm bombs, use a new type of parachute, fight forest fires, and survive in remote forested areas.[6]

References

- ↑ Henry L. Benning. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021

- ↑ Fort Benning Army Base Guide. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fort Benning, GA History. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021

- ↑ O’Brien, Connor. "Scrubbing Confederate names from Army bases gains steam in Congress, but fight with Trump looms". POLITICO. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Simon, Scott. Opinion: Let's Rethink The Names Behind Forts Benning And Bragg. June 13, 2020. npr.com. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Aney, Warren. UTriple Nickles -- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. July 6, 2020. oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021